After two years almost continuously at sea, the CSS Alabama was starting to show her age. In June of 1865, she sailed into the harbor at Cherbourg, France, to seek repairs and coal. During the war, technology had improved, and so her arrival was quickly announced to The U.S.S. Kersarge, a battleship that soon arrived to stand guard at the mouth of the harbor. Despite the condition of his ship, Semmes sent a message through consular channels that he would gladly fight the Yankee:

After two years almost continuously at sea, the CSS Alabama was starting to show her age. In June of 1865, she sailed into the harbor at Cherbourg, France, to seek repairs and coal. During the war, technology had improved, and so her arrival was quickly announced to The U.S.S. Kersarge, a battleship that soon arrived to stand guard at the mouth of the harbor. Despite the condition of his ship, Semmes sent a message through consular channels that he would gladly fight the Yankee:

"I desire to say to the U. S. consul that my intention is to fight the Kearsarge as soon as I can make the necessary arrangements. I hope these will not detain me more than until to-morrow evening, or after the morrow morning at furthest. I beg she will not depart before I am ready to go out."

It is believe to be the last instance in which a formal challenge was presented by one commander to another. And it was to become the last major battle between sailing ships. Steam would soon be the propulsion method of choice for battleships.

On June 19, 1864 the two ships met seven miles off the coast and engaged in an hour long battle. The ships steamed in a series of circles, firing all the time. One Alabama round lodged itself in the Kersarge stern post, unexploded. At President Lincoln's request, that section of the stern post was later cut out and delivered to Washington as a trophy of war. It is still on display in D.C.

The Alabama had always had a problem with damp gunpowder, and in this final battle, that was one of the factors that doomed her. Many of her shells failed to explode. After an hour, she was sinking, and the battle was over. Semmes reportedly threw his sword into the sea to prevent it from being captured by the enemy, though Kell's wife would later quote her husband as saying that was not true.

Twenty six CSS Alabama crewmen died from wounds or drowning , while The Kearsarge lost only a single man. Yankee newspapers celebrated:

“The pirate Alabama has at long last gone to the bottom of the sea. After a bloody and lurid career…she has been annihilated on the very first occasion* that one of our-ships-of-war was enabled to get an opportunity to measure metal with her.” [The New York Times, July 6, 1964] (*The Times was conveniently forgetting the U.S.S. Hatteras, which lay on the bottom of the Gulf of Mexico off Galveston, courtesy the guns of the Alabama.) Southern papers mourned her loss, while saluting her bravery: “It is safe to say The Alabama has paid for herself five hundred times. She could afford to die,” offered one Richmond editorial writer.

There was almost as much controversy about the CSS Alabama's end as there had been about her life. As the ship sank, a pleasure steam yacht, The Deerhound, swooped in and managed to save almost all of the Alabama's officers, including Semmes, whose hand was injured by a part of a shell or a splintered piece of wood during the battle. (You can see him with his injured hand in the photo below, taken shortly after the battle. With him the doctor who treated his hand, and Kell.) The yacht that saved Semmes was owned by a confederate sympathizer who quickly took the men to the English shore. There were allegations that the Deerhound was in position for that very purpose, though they were denied. Critics suggested that Semmes, his ship lost in a fair sea battle, had an obligation to present himself to the victor as a prisoner of war.

[NOTE: There is an eyewitness account of the final battle posted on the blog Bob Corley and I started as a companion to the planned documentary. You can read that post here.]

[PHOTO: An actual banner from the CSS Alabama, saved as the ship went down in the English Channel on June 19, 1864. It is in the collection at The Museum of Mobile.]

Instead, after recovering in an English Hotel, Semmes made his way back to Confederate Territory, was made commander of a fleet of ironclads on the James River in Virginia, eventually fled further South as the Northern forces advanced in the final days of the war, and finally surrendered in Greensboro, North Carolina.

Paroled, he settled back in Mobile until a patrol of Marines showed up on December 16, 1865 and arrested him at his home. They carried him by boat from New Orleans to New York City and then to Washington. He was imprisoned in the Washington Navy Yard.

Soon afterwords, the war was over. Lincoln was dead of Booth’s bullet, and in the aftermath, the Johnson Administration couldn't agree about prosecuting Semmes. After four months in custody, he was released.

Home again in Mobile, Semmes kept fighting the war and the Yankees, who would not allow him to hold elected office during Reconstruction. Semmes became the quintessential unreconstructed rebel.

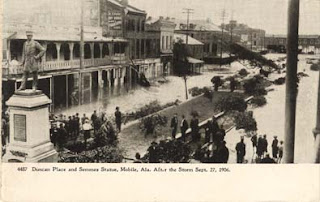

He died on August 30, 1877, days before his 68th birthday, from food poisoning after a seafood dinner. On the day of his funeral, cannons are fired every hour and thousands gather in a pouring rain to honor him. In Mobile, a statue of him was erected in 1901.

Fast forward to more modern times...1984.

A French minesweeper is conducting training exercises in the Channel. As by custom, one of the targets they search for is the long missing wreckage of the CSS Alabama. But on that day, they found it! After an international squabble over rights that lasts several years, a joint French/American operation charted the wreckage and brought up artifacts, including several of the ship's cannons. Conditions at the wreckage are so difficult, it is unlikely any additional parts of the confederate raider will be brought up. But at the Museum of Mobile in Alabama and a naval museum in Cherbourge you can see some of the relics and learn much more about the Alabama than I've shared in this brief series. The U.S. Navy also maintains an informative site.

[ADDENDUM: During my research for the documentary that was not to be, I read a dozen books or more on Semmes and his ships, and even purchased some historic documents, like those shown above. One of the most recent books to tackle the story was by Stephen Fox: Wolf of The Deep, and it was in fact Fox who first suggested a documentary on Semmes and the CSS Alabama. My August 2007 interview with him was my first real exposure to the story, but certainly not my last. I must note that Semmes' Great-Great Grandson Oliver dislikes parts of the Fox biography. Still, Oliver Semmes was kind enough to share his intimate knowledge of his ancestors with us, as was the staff of The Museum of Mobile (where you can see artifacts from the ship, including her restored bell and her commodes!) and many others. Oliver also shares Raphael's birth date, and turns 80 today, so Happy Birthday to him!

I have only skimmed the surface of the Semmes/CSS Alabama story in these blog postings. In addition to Fox's Wolf, I recommend Confederate Raider by John Taylor, The Alabama & The Kearsarge by William Marvel, The Philosophical Mariner, by the late University of Georgia professor emeritus Warren Spencer, and of course, Raphael Semmes own volumes. I would like to recommend Ghost Ship of The Confederacy, a 1957 volume by William Boykin, but it is long out of print and, in my view, contains so much undocumented (but quite fantastic) material that I am hesitant to trust it. Boykin was an advertising man, which may explain some of the great details of which he seems to be the sole proprietor.

A great resource for additional study is the University of Alabama Hoole Collection, which includes the original CSS Alabama plans (which were retrieved from the trash at the Laird Company in England!). In Montgomery, The Alabama Department of Archives and History collection includes Semmes' log books, letters, and even some of the bonds he took from ships that he did not burn, though those items are not generally on display. Here is a drawing from Semmes's logbook in which he explained how to escape a hurricane in a ship! It is believed to be the first such drawing by a ship's captain.

I thoroughly enjoyed writing (and recording) these posts, and I hope you enjoyed reading them. Perhaps some day the documentary Bob and I planned will come about. In the meantime another book in what seems to be a never-ending stream of volumes about The CSS Alabama, the war, and the Confederate Navy has been published. Read about "The Most Perfect Cruiser" here on the British website "When Liverpool Was Dixie".

And Please do comment on the series, and let me know where you live!]

I thoroughly enjoyed writing (and recording) these posts, and I hope you enjoyed reading them. Perhaps some day the documentary Bob and I planned will come about. In the meantime another book in what seems to be a never-ending stream of volumes about The CSS Alabama, the war, and the Confederate Navy has been published. Read about "The Most Perfect Cruiser" here on the British website "When Liverpool Was Dixie".

And Please do comment on the series, and let me know where you live!]

I've appreciated this series, Tim. YOu are champ!

ReplyDeleteSince you asked--I live in Old Cloverdale, where you need the city's Architectural Review Board's permission to paint your front door a different color.

Quite simply, a most marvelous series, Tim! And one which I thoroughly enjoyed reading!

ReplyDeleteThanks for sharing!

(Though I'm certain you know, and greatly suspect your regular readers may as well, I'll state For The Record, that I'm a resident of Huntsville, AL - the state's first capitol city, where the state's first constitution was drawn, and "Where the Sky is NOT the Limit!")